Tile Trivia is a sideways glance at the decorated history of tiles. We’ll delve into a different story each time, taking you on a journey that stretches thousands of years – from the very first pieces of painted pottery to the space age materials on the Shuttle and beyond.

For the second instalment in this series, we’ll be taking a look at the wonderful world of Victorian tiles.

I think we’d all agree that the Victorians were a pretty enterprising lot. Not content with kickstarting the industrial revolution, they gave us plenty of things we take for granted today. Railways. Electricity. Compulsory education. The Penny Farthing.

Oh, and they left us some pretty nice buildings too.

Like many of us, I’m lucky enough to call a cosy Victorian terrace home, work in a converted Victorian mill and live in Manchester, a city stuffed to the brim with with handsome buildings knocked up during the long, long reign of Queen Victoria. Maybe I’m a little biased, but give me Manchester’s gothic town over the Guggenheim any day of the week.

But I guess I’m not the only one – if I asked a group of people to name their favourite style of architecture, I reckon there’d be a fair show of hands for Victorian. Not bad for a style that withstood the triple whammy of two world wars and a Sixties strip out.

But why do we love them so much? Ask an estate agent and she’ll tell you her buyers love the interesting features – the grand staircase, large sash windows and the cast-iron fireplaces. An architect will mention the high ceilings and attention to detail. A builder would wax lyrical about the solid walls and how the homes were built to last for generations.

And me? Why do I love Victorian properties so much?

Well I’ll give you a straight answer – it’s all in the tiles.

A couple of years ago I was in the process of buying a Victorian house. Never mind the local schools, whether it has a south facing garden or what the neighbours were like… the deal clincher for me? The fireplaces still has their original tiles! I mean, why worry about the ancient plumbing or the damp walls when there were original tiles in the bedrooms? Ever seen a grown man go weak at the knees? The estate agent did that day.

Once we picked up the keys it became apparent the house was missing a fair few things. Those original encaustic tiles I secretly hoped to find hidden under generations of life? Gone. Skirting boards one foot high? Nope. Pretty much anything you and I would deem to be ‘character’ had been ripped out during a post war moment of madness. I guess the fireplaces and their tiles only remaining because even a madman wouldn’t take on a cast-iron fireplace and win.

Oh well. Times change. I get it.

But luckily, there’s a whole world of modern reproductions out there, looking for a new home in an old house. They’re perfect if your place has been stripped bare, or if you want to give your modern building a period makeover.

And so…. drumroll…. here’s the official Porcelain Superstore guide to our Victorian-style tiles.

Patterned floors

Back in the early 19th century a new architectural movement sprang up – gothic revival. And if you’ve never heard of Gothic Revival then you’ve certainly seen it – the Houses of Parliament, Liverpool Cathedral and Manchester Town Hall are three famous examples.

As the name suggests, this style was heavily influenced by gothic buildings from the Middle Ages. So on the outside you’d see pointed arches, steep-sloping roofs and plenty of ornament. And on the inside, you’d find an exquisite patterned floor, often covered in fleur-de-lis and quatrefoils designs.

Back in medieval times, these patterns were used to ornament cathedrals, monasteries and homes of the wealthy. After falling out of fashion, they were re-discovered hundreds of years later by the Victorians and in particular a certain Mr Herbert Minton. A man we can confidently call one of the greatest entrepreneurs of his generation.

Born into a family of potters, Minton combined his family’s knowledge of ceramics with new methods of production and developed industrial techniques for producing decorative tiles. Known as encaustic tiles, they were made by layering different colours of clay – so a single tile would essentially contain a pattern that ran the whole way through the tile.

Pretty soon Minton tiles were being laid in the House of Parliament and further afield and Minton was on the way to becoming the largest tile producer in the world. However, their exquisite tiles still commanded a relatively hefty price tag so only the rich and famous could afford a Minton floor. And even then, they would only be laid in areas that guests were likely to see – entrances, hallways, entertaining rooms and the like. Did someone say the Victorians like to show off their wealth?

You can achieve a similar look with our ceramic Tapestry tiles. Thankfully, they cost a lot less than their Victorian equivalents so you can use them anywhere inside your home without breaking the bank.

Geometric Floors – Part One

So, the Victorians loved their patterned tiles but there was one small problem – their expense meant that only the very rich could afford them. And even then, their use was limited to entrances and hallways – the areas you’d want to impress.

Thankfully – for us as much as the Victorians – a bright spark soon discovered a more cost effective alternative. Producing a tile with an embedded pattern was expensive, but producing a tile with just a single colour was relatively cheap. So by laying together two or more colours of these cheaper tiles together, in a repeating pattern, the geometric floor was born. Or reborn, because it was popular in Roman times, but that’s another story.

Unlike the patterned floor tiles above, where each tile contained pattern and different colours, in a geometric floor each individual tile was only one plain colour, and as a result was far cheaper to produce. And of course, all this was happening at the same time as the industrial revolution, so all of a sudden mass manufacturing meant that these geometric floor tiles were pretty cheap.

So at the simple end of the geometric scale, we get the classic checkerboard effect – the mix of black and white squares together. It’s a simple, timeless look – just walk past any row of Victorian terraces and we’ll wager that you’ll see some original monochromatic tiles decorating their front pathway and porch. It shows how durable these tiles are, when you think of all the wear and tear they have to contend with. And the bad weather.

You can achieve the same effect with our Dorset Black and Dorset White tiles – they’re made in almost exactly the same way, so they’ll hopefully still be at your house in another 100 years.

Geometric Floors – Part Two

By the mid nineteenth century, demand for patterned tiles had shot through the roof. Our friend Herbert Minton must have been enjoying himself – alongside commissions for the Victoria and Albert museum and Westminster Palace, he received plenty of orders from around the far flung corners of the Empire. Oh, and a not-so-insubstantial order from the US to supply tiles for the Capitol building in Washington DC. Not bad for a lad from the Potteries!

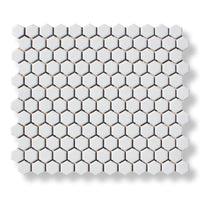

The middle classes of Victorian Britain wanted their slice of patterned pie too – and the checkerboard alone wouldn’t do. So canny manufacturers did what canny manufacturers do best – they gave the customers what they wanted and started producing their tiles in all manner of shapes and sizes. Triangles, diamonds, lozenges and hexagons – you name it, they made it – and the Great Victorian Public went crazy, mixing and matching different colours and shapes to their hearts’ content. They soon became the go-to covering for any self-respecting Victorian household from Aberdeen down to Brighton and homeowners could opt for whatever their heart desired, from the rather simple to the very elaborate.

Many of us are lucky enough to have an original geometric floor. But if, like me, you’re not one of them then you don’t need to pay an eye-watering amount of money for reclaimed tiles. Instead, high quality modern replicas are available, such as our Abbey Decor and Richmond Mosaic patterned floor tiles. These are made from porcelain, so they’ll last just as long as Minton’s finest and each tile features life-like grout joints to give the impression of individual tiles.

Back in the nineteenth century, laying individual tile pieces together was a laborious and expensive process that only the most skilled tilers could undertake. And once laid,a housemaid would have the unenviable task of scrubbing, waxing and buffing the tiles, to stop the natural clay absorbing dirt and grime. Once a week!

By their nature, our tiles are far easier to install and care for and honestly, once they’re laid you’d be hard pushed to notice the difference. Although you’ll definitely notice the difference between paying for these and some expensive original geometric tiles!

Wall tiles

Given that the Victorians had a known weakness for pattern and pomp, we’d be forgiven for thinking they were all flash and showy. Far from it!

In fact, the Victorians also loved floor tiles because they were so practical and easy to keep clean. Remember, this was a time of tenement blocks and crowded terraces – and the connection between health and hygiene was starting to be understood. Compare how easy it is to clean a flat tile compared to a pitted floorboard and you’ll know exactly why they were tile crazy.

So onto bathrooms… Well actually, the idea of the bathroom didn’t really exist for the majority of Queen Victoria’s reign. It was only towards the end of the nineteenth century that Thomas Crapper and produced the thankfully-now-ubiquitous flushing loos his names is now synonymous with. Prosperous Victorians latched onto this new fashion and hastily converted their dressing rooms into what we now call bathrooms – no more chamber pots or ‘privies’ at end of the back yard for these posh folk.

In a bid to save a few pennies – pennies to be spent on clawfoot baths, of course – our Victorian friends looked for a relatively cheap and easy-to-clean covering for their new designer space. These private rooms were way from the prying eyes of guests, so plain and simple would do just nicely. And the factories based in the Potteries – that’s Stoke on Trent to you and me – were only too happy to oblige with their glazed ceramic wall tiles. Pale colours were the order of the day – with the all-white colour scheme particularly popular. So I guess somethings never change, do they?

If you’re looking to recreate a Victorian-style bathroom at home, metro tiles are a great place to start. For maximum points, lay brick bond and install a traditional freestanding tub. But don’t be afraid to mix dark and light tones together. Our Victorian Green and Victorian Plum metro tiles are inspired by the darker colours used in Victorian sitting rooms but make a great choice for modern homes.

Plenty of original period tiles now have crazed surfaces, where the glaze has cracked over time. This is part of the appeal of age-old tiles, so if you’re fortunate to have these in your home, cherish them! If not, crazed wall tiles such as our Crackle Glaze range are available that combine the hand-made character of old with light, contemporary shades. They’re an ideal choice if you’re after a blend of the old and new. Just remember to tell your tiler to seal the surface before grouting!